Recently, I have come across plenty of articles and videos discussing Vin Group’s debt burden. There’s already plenty of commentary out there, and on a personal level, I don’t want to get caught up in debating the accuracy of those sources.

What I would rather do is point out three common traps that, in my experience, often trigger liquidity crunches. I have come across these patterns time and again in practice, and sharing them might offer a sharper perspective on liquidity risk and how debt should be managed strategically.

Table of Contents

Where does debt come from?

First, let’s take a step back and unpack where debt really comes from. In my view, it ultimately traces back to three fundamental corporate finance choices, questions every CEO and CFO must confront head-on.

- Which investment strategies should a company pursue to maximize Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) while preserving its long-term competitive advantage?

- How should the capital structure be designed to fund those investments at the lowest possible cost of capital?

- How can the company ensure operational stability and avoid cash shortages while executing (i) and (ii)?

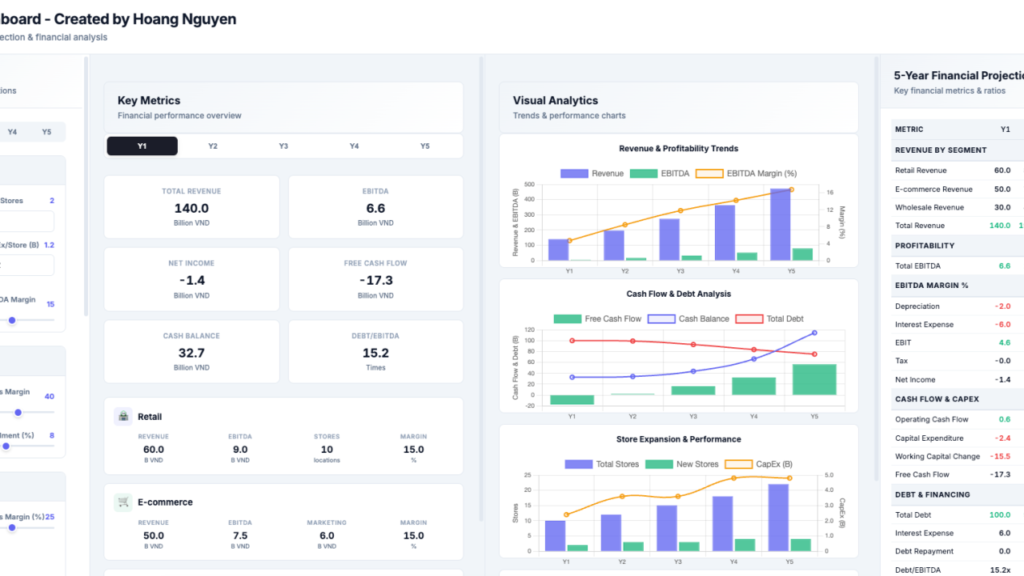

If you pay close attention, all three of these decisions are generally reflected in the financial statements, particularly the cash flow statement and the balance sheet. For me, they are the key areas to assess a company’s financial health and management capability. Evaluating the third question, however, requires a deeper understanding of how cash flow operates, both in its “direct” and “indirect” forms. It also means being able to read a balance sheet through the lens of “sources and uses of funds” and building a practical, reliable cash flow forecast that can support sound judgment.

I usually start this process by consolidating financial statements over the past three to five years to just answer one simple question: during that period, did the company generate cumulative cash flow to sustain itself and reinvest, or did it have to rely on external funding? If external capital was needed, where did it come from, and when must it be repaid? You might wonder why I look at several years instead of just one. My answer is simple: cash flow tends to swing in the short term (especially for working capital intensive businesses), due to seasonality, timing differences between transactions and reporting, or sometimes deliberate accounting choices designed to tell a certain story. But in the long run, the true drivers always reveal themselves.

Put simply, if a company’s operating cash flow after covering capex plus its opening cash balance is still negative, then it needs to raise additional external funding. That’s when debt shows up.

The classic stories

Circling back to the traps I mentioned earlier. In my experience, short-term cash crunches often trace back to three familiar patterns, which I like to call the classic liquidity risk stories. I’ve seen them repeat across industries and cycles. And frankly, businesses that fall into these traps are the ones I tend to avoid of when building my portfolio.

Story No. 1: Debt leverage as poison

When structuring capital, the first question is always: what is the company going to do, and what does it need? Many businesses fall into the debt trap, over-leveraging in the belief that future operating cash flow from the investment will cover both interest and principal. The reality, however, is that projects often underperform, due to unforeseen market variables or simply weak risk management. Liquidity risk arises right from the capital structure design stage when finance architects “ignore” potential risks, leading to a duration mismatch between funding and operating cash flows.

In my view, debt is a double-edged sword: a powerful lever if used wisely, but a deadly poison when abused. If future cash flows are uncertain and financial flexibility is limited, whether due to weak balance sheets or restricted access to capital, it’s best to treat debt with caution.

Story No. 2: Paying dividends before being “ready”:

Another common basic mistake I see is companies failing (or refusing) to distinguish between profit and cash flow. They report profits and distribute dividends regularly, while free operating cash flow remains negative year after year, and debt keeps ballooning to fill the gap. Why pay dividends then? In many small and mid-sized firms, especially where ownership is concentrated with the founder, dividends often serve as a channel to funnel money into real estate investments, a popular path to wealth in Vietnam.

But when the business environment turns, the consequences hit hard. Without proper management, the short-term personal gains of shareholders can end up costing the company its long-term survival.

Story No. 3: The price of growth:

On another front, countless businesses chase growth because of the allure it creates externally. But behind the story of growth lies risk if it’s not managed well. Growth almost always demands more working capital (especially in manufacturing, textiles, agriculture, and retail) or prolonged cash burn until breakeven, leaving cash flows negative for years while “profits” are tied up in receivables and inventory. Why? To grow quickly, companies often compromise on customer credit terms and margins when product demand isn’t strong enough. To prepare for sales, they also stockpile more goods. Overtrading risk eventually surfaces, particularly when receivables are of poor quality or inventory isn’t well managed, making it harder to convert into cash later.

I believe every business owner, CEO, CFO, and leadership team should constantly challenge themselves with the most fundamental strategic question: is the Company using cash to grow, or growing in order to generate cash? The answer generally lies in balancing strategic ambitions with liquidity risk.

Conclusion:

The outcome of these stories is often the same: companies scrambling to roll over debt when it comes due. If capital markets are tight, investor confidence fades, or cheap funding dries up, they’re immediately in trouble once the business environment shifts. At that point, survival requires painful sacrifices, cutting costs, selling off underperforming assets, or in the worst cases, declaring bankruptcy.

Those bring me back to the point: in hard times, everything reverts to fundamentals. The ultimate purpose of business is to simply generate surplus cash. Why? Because only cash can repay debt, settle obligations, reinvest, pay dividend, and keep the company alive to fight another day.